Public Lecture|Patterns of Macanese Migrations, Cultural Development, and Identity

Public Lecture|Patterns of Macanese Migrations, Cultural Development, and Identity

12

Nov

The history of Macau and its people is also the history of Macanese culture as it developed during several migrations and resettlements across Asia that began from the middle of the 16th century…

DATE & TIME

12 November 2014, 18:30 – 20:00

VENUE

Speakers Hall, University of Saint Joseph, Rua de Londres 16, Macau, China

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

Dr. Roy Eric Xavier received his Doctorate and Master’s degrees in Sociology from the University of California, Berkeley, where he is now the Director of the Portuguese and Macanese Studies Project, and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for the Study of Societal Issues. Prior to Berkeley, he was an Associate Dean at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, and earlier the General Manager of KCRT Television and Media for 14 years in Richmond, California.

His recent publications include: “Death at the Races: The Portuguese Presence during the Happy Valley Fire of 1918”, published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society – Hong Kong, Vol. 53, March, 2014, and “The Macanese at War: Survival and Identity among Portuguese Eurasians during World War II”, to be published in a collection by the University of Hong Kong in early 2015.

ABOUT THE TALK

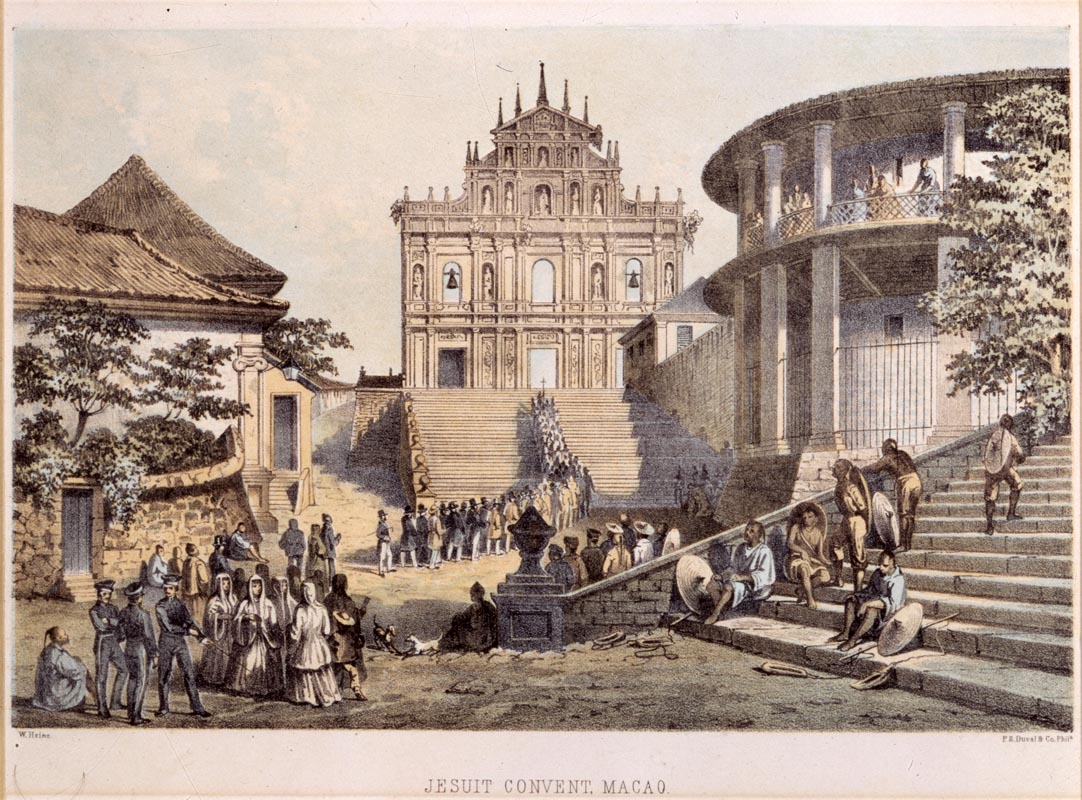

The history of Macau and its people is also the history of Macanese culture as it developed during several migrations and resettlements across Asia that began from the middle of the 16th century. These migrations were the result of Portuguese expansion and trade, which at its height stretched from the Persian Gulf to the northern coast of Brazil. The settlement of racially mixed Portuguese in Goa, Macau, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and other ports along the trade routes also marked the locations where forms of a new “maritime” culture in Asia first appeared.

Beginning in 1557 the emergence of Macau provided neutral ground for Europeans and merchants from Asia to exchange goods, and a tolerant environment where Portuguese Eurasians could settle in relative peace. During the next three hundred years, various elements of “Macanese” culture and identity solidified, including a creole language, religious devotion adapted to the conditions, an expressive literature, and culinary arts. Some components were encouraged by the Church, while others were influenced by the continual mix of people who traveled in and out of Macau as trade with Europe developed.

At a macro level, Macanese culture and identity first took root in the lore of Portuguese explorers, including Henry the Navigator, Vasco de Gama and Jorge Alvares, whose discoveries of sea routes to Africa, India, Asia, and South America allowed the Portuguese to by-pass the old “silk road” that linked Europe and Asia from the time of the Crusades. These explorations were driven in large part by the need of the Portuguese monarchy to be less dependent on Spain in the 15th and 16th centuries, a period of political and social upheaval in Europe which we now identify as the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance.

To secure their early advantage, the Portuguese sought to incorporate, rather than conquer, indigenous peoples into a colonial strategy that was later adopted by other European rivals. When the number of Portuguese in Asia began to dwindle after 1600, this same policy led to the recruitment of mestizos in Macau and other trading ports as soldiers, artillery gunners, navigators, linguists, advisors, and mid-level bureaucrats. Many in Macau served as intermediaries to the Chinese Empire, Portugal’s principal trading partner in the 17th century, and played key roles in the creation of European trade and the beginnings of global commerce.

Thus, the emergence of Macau as the cultural home to Portuguese Eurasians contributed to socio-economic developments that had direct consequences in Europe, the Americas, and rest of the western world. A closer look at Macanese migrations and the relation to culture and identity through case studies allows us to illustrate how this important variant of cultural development occurred over the last five centuries.

ORGANISER

Faculty of Humanities, USJ

SPONSOR

Macao Foundation